I heard a teacher say the other day, “I am trying to kill the notion that fiction is fake. I am teaching them that in fiction, we learn through imagination.” I love her laudable goal, as I have learned just as much theology through fiction as I have through theology works. In fact, works of fiction have a way of wriggling the Scriptural truths that I know down from my head into the very warp and woof my heart. When I read a work of fiction that especially strengthens my faith and stirs my soul for God, I try to recommend it.

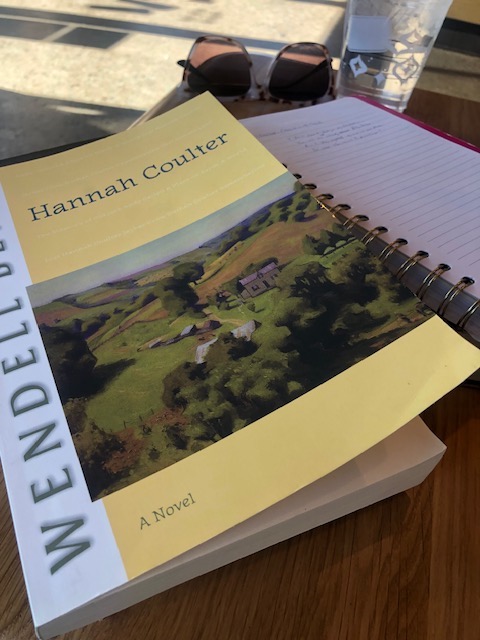

If you know me, you know my love for Wendell Berry, which is why it is surprising, even to me, that I have not written about his novel Hannah Coulter until now. In my present season of parenting teenagers and learning how to release them, God has given me a mentor in the form of the fictional Hannah Coulter. In light of the wars in Israel and Ukraine, Hannah Coulter has been teaching me about hope that coexists with grief. As I approach my middle-aged years, Hannah is helping me learn to embrace the beauty of sameness and stillness. As such, it is fitting that I would want to proudly introduce you to my (fictional) friend from the semi-fictional Port William.

Hannah’s Hope Amid War & Grief

Having married her first love, Virgil, in the fall of 1941, her days of early wedded bliss were interrupted by World War II. In her own words, Hannah writes, “There was an ache that from time to time seemed to fall entirely through me like a misting rain. The war was a bodily presence. It was in all of us, and nobody said a word.” I have felt, even from far off, the falls of those misting rains as war once again scars our world and scatters precious people. Hannah captures it better than I can: “A great sorrow and a great fear had come into all the world, and the world was changing.”

Hannah’s world changed drastically, as she gave birth to her daughter while her husband while her husband was declared missing at the Battle of the Bulge. She learned to love an infant while grieving the loss of the love that brought her into existence. Her thoughts on grief have shaped me:

“But grief is not a force and has no power to hold. You only bear it. Love is what carries you, for it is always there, even in the dark, or most in the dark, but shining out at times like gold stitches in a piece of embroidery.”

Through the love of the township of Port William, who in her words, “were always trying to the blank they felt around me,” Hannah began to emerge out of her grief and back into hope.

“I began to trust the world again, not to give me what I wanted, for I saw that it could not be trusted to do that, but to give unforeseen goods and pleasures that I had not thought to want.”

Grief had changed her view of the world, but it had not broken her heart to hope. The world would be full of trouble, but it would also open up its storehouses of beauty and bounty. Hannah’s grief is training me for whatever pain, picayune or poignant, the Lord will bring my way. Beauty and brokenness coexist, so to close our heart to one is to miss the other.

Hannah’s Hope Amid the Mundane

Over time, Hannah finally gives in to the patient pursuit of Nathan Coulter, a veteran who, unlike her first husband, survived the war. The horrors of the war drove Nathan towards a love for his hometown and farming. The strains and stress he bore pushed him until he was planted for life on a lot of land that he loved— that together, they loved.

Hannah talks about the value of loving the place where you live:

“You walk up and stand beside it, loving it, and you know it doesn’t care whether you love it or not. The stream and the woods don’t care if you love them. The place doesn’t care if you love it. But for your own sake you had better love it. For the sake of all else you love, you had better love it.”

I’m not a farmer. I cannot even grow my garden well for long. But I have been learning so much about the power of place. In a transient, ever-upward-and-outward-scrambling culture with a restless soul, I am slowly learning the value of being present right where my feet are standing. As we plant a church, I am learning to love the local in a way that it is hard to put into words. I love our quirky little flock of God. I love our borrowed (and mostly cut-and-pasted from the eighties) church space. I still don’t love our poorly paved neighborhood roads, but I wonder if I might one day.

Hannah’s Hope as Children Move On

I saved the most significant for last, as, more than anything else that I learned from reading Hannah Coulter, I learned to both celebrate and grieve the changes of parenthood. Few things are as close to my heart as motherhood, because there are very few things I have given myself to more. Motherhood has made me and is making me still.

The love I have for these three boys of mine is so strong that it actually scares me from time to time. I honestly tremble at the tenderness and terror I feel in my heart for them. Having chosen to give myself almost entirely to raising them, I find myself fearing the changes that are emerging as they are closer to being raised and ready to stand upright apart from my buttressing roots.

Hannah Coulter captured the emotions that are emerging in me in ways few people have yet:

“When they were young, I suppose all my thoughts about the children starting with knowing they were mine….Now all my thoughts about them start with knowing that they are gone.”

While my children are not adults yet, I am already grieving the greater distances they travel from me spiritually, emotionally, and physically. A week when they are away at camp feels like a year. Hannah writes the following:

“To be the mother of a grown-up child means that you don’t have a child anymore, and that is sad. When the grown-up child leaves home, that is sadder…Maybe if you had enough children you could get used to those departures, but, having only three, I never did. I felt them like amputations. Something I needed was missing. Sometimes, even now, when I come into this house and it sounds empty, before I think I will wonder, ‘Where are they?’.”

When someone can put into words what you inaudibly feel, they give you a gift. Hannah gave me the gift of being seen and known in places that feel tender to me at present.

Learning to Live Right On

Throughout the hills and valleys of their marriage and parenting, Nathan consistently tells Hannah and their children, “We’re going to live right on.” While this response may seem simple, it has shaped me. His response to a cancer diagnosis and a wayward grandchild, as well as the other ordinary fears and fissures of life on a broken world, was the simple, stalwart reassurance that they would live right on through it. Lately, when hard things hit, I find myself repeating, “We are going to live right on.”

Hannah and Nathan Coulter, fictional mainstays in a mostly fictional town, have invited me into their home like an aged mentor couple. They have showed me what embodied hope looks like in a broken world. I hope you get to meet them one day. Thanks, Wendell.

Leave a comment